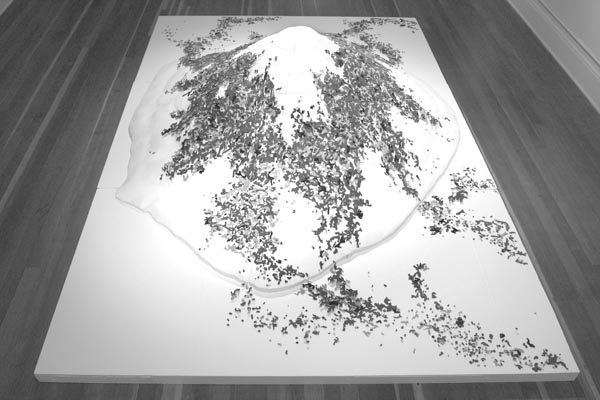

Happy Mountain—Japanese Landscape, Installation view at Mission

17 33”x192”x144”, felt, pin, polystyrene

2004

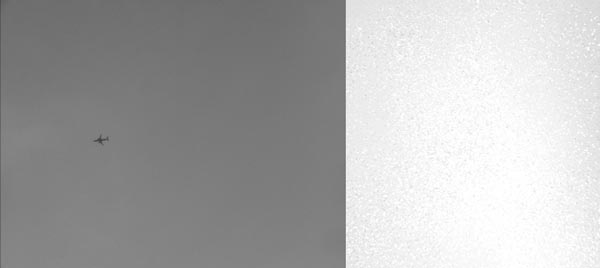

Streak Of

archival inkjet print, 23.25”x24” and 23”x31”

2006

Mayumi Hamanaka’s Fickle Topography

by Monique Montibon

A PHOTOGRAPH of a lone bird soaring against the backdrop of a cloudless blue sky— it’s a fleeting moment captured in a split second, but such a mundane or perhaps even seemingly insignificant occurrence evokes a broad range of sensations in its observers: freedom, loneliness, bravery, fear, beauty and impermanence, among others.

No two people experience life in exactly the same manner, as our preferences and prejudices are shaped by myriad influences. Add to this the fact that our opinions and those myriad influences continually change, and it starts to become apparent that it’s a tall order to formulate one’s identity within the context of such a fickle world. This notion is an important concept behind Mayumi Hamanaka’s work.

It seems difficult or even frustrating to grasp one’s sense of meaning or the significance of one’s place in history during an era in which a plethora of conflicting information and media messages are competing for our attention, but via her art, Hamanaka asks us to try.

She draws attention to the intersection of the intentional and the incidental, and reveals the extraordinary in the ordinary, often by juxtaposing two seemingly disparate images. An extreme close-up photograph of a flower, for instance, causes the flower to lose its solidity as a recognizable object, yet being so close to it reveals sensual textures and brilliant colors that may otherwise be overlooked. Placed beside a photograph of an airplane in flight—so high in the sky that its shape resembles a small gray shark in a large dark ocean—the two images together illustrate the impermanence of life: A vibrant flower becomes an omen of the impending end of every life cycle, an airplane overhead never again repeats that exact trajectory. Together the effect is beautiful and ethereal yet laced with a distinctly ominous feel. Or perhaps it is the suggestion of our own mortality that lends a subtle air of doom to the piece.

Through her work as an installation artist and photographer, Hamanaka brings to each discovery an awareness of the inherent, ephemeral quality of life, as well as an understanding of how this in turn impacts us and our impressions of everyday existence. It is human nature to be caught up in the past or focused on the future, due to our tendencies to grasp at what we love and avert from what we dislike, but Hamanaka’s work welcomes the viewer to the present; it serves as an invitation to consider one’s place in time at this moment and utilizes reconfigured images of the past for context.

At a recent joint exhibition at Swarm Studios in Oakland, some of Hamanaka’s pieces resembled white topographic maps. Upon closer inspection, the viewer could see they were actually photographs that were taken during World War I and World War II and recently reworked by Hamanaka. Clusters of bodies were outlined as amorphous shapes on white paper, which were then carved out and stacked upon one another, each layer incrementally smaller than the previous one—hence the cartographic relief effect. Appearing in nonchronological order, and devoid of any details that could possibly date the images, they gave the viewer the opportunity to see familiar scenes with fresh eyes, and to consider their lingering significance. It is one way to experience Hamanaka’s work, and arguably, an underutilized way to experience life.

For more information about Mayumi Hamanaka, go to studioislander.com.

Monique Montibon is the former editor of Reverse Angle. She thinks about her own mortality too much.