I Was a Teenage Mouse Jockey

My Life Among the Lucasites

by Lisa Drostova

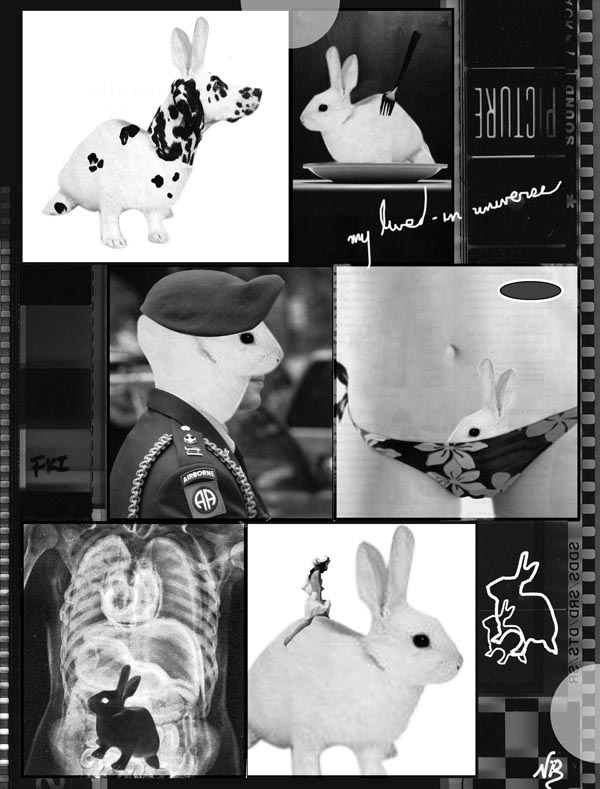

illustration by Nina Bays

IF YOU’RE watching the original Star Wars trilogy quietly by yourself, and can get past the question of whether Han shot first, you might notice something interesting. The lightsabers vary. Not just from film to film, which you would expect of any series produced over several years. Not just from shot to shot. Sometimes within a single shot, the way two lightsabers move is completely different. One bends as it swings through space while another remains rigid. One is slender for its whole length, while another is much wider at the base than the tip.

It’s a charming idiosyncrasy, and one George Lucas was determined to stamp out when he created the new trilogy. Which is why, in 1998, I was sitting in a Marin County screening room surrounded by men ranging from their mid-20s to late 50s, watching a reel of lightsaber fights spliced together from the original films. No sound, no dialogue, just duels: Obi-Wan versus Darth Vader, Darth Vader versus Luke, Han versus that poor dead thing with the laundry-hose innards. We were going to develop a consistent lightsaber look and behavior that would set the standard for Episodes One through Three.

I believe I was the only person in the room who hadn’t been dreaming since childhood about working for Industrial Light and Magic, which is probably why I was the only one who wasn’t making the sound. Yeeeeang. Eeeeeywiiing. Shwwwuuuuh. The lightsaber sound. So quietly at first you might miss it, and then at increasing volume, my coworkers were losing themselves to the children they had been when the films first came out, blown away by the vision of a “lived-in universe” that was light-years beyond anything that had been put to film before, a place where an uneducated punk kid from the boonies could save the universe with a bare minimum of training but plenty of resourcefulness, spirit and a lead foot.

Working for a company where your coworkers openly admit that they’ve built themselves lightsabers—as adults, from scratch because the kits aren’t realistic enough—is a little weird. After a while I started to think it was a prerequisite of employment and wondered how I, who had owned one of the cheap pre-made flashlight ones as a kid, had ever managed to get a job. But then there was a lot that was strange about being at ILM in the ’90s, just when the FX industry was making the transition from physical models and sets to whole creatures and worlds built entirely of pixels. Only now, nearly a decade after I threw down my mouse in exasperation, am I starting to see how odd it was.

It’s Not Tracing

I made a living drawing lines around things. As a rotoscoper, a kind of animator, I used to explain my job by holding up whatever was closest—a pen, a salt-shaker, a surprised chihuahua—and waving it around. “There’s this synthetic element,” I’d say, “your dinosaur or monster or spaceship, and it has to merge perfectly with the live-action background. I make the element” (and here I would trace a finger in the air around the chihuahua) “that keeps either the foreground or background opaque, making the illusion possible, so that one doesn’t show through the other.” For years, I watched people’s eyes glaze over. “Just tell them you draw the dinosaurs,” my mother advised, “that’s what I’ve been doing.” I also cleaned things up, added shadows and light effects, and removed stray stuff: wires, boom mikes, Gary Sinise’s lower legs. I can separate blond hair from a bright sky, shattering auto glass from the street scene behind it, flying water droplets from a pirate ship’s bow. In other words, I spent seven years being a professional compulsive, at a company where that kind of sickness was encouraged.

When I started at ILM, I was 21, with a bachelor’s degree in anthropological linguistics. My professional experience consisted of waiting tables in a sandwich joint and assisting in a Minneapolis animation house. At my ILM interview I described how I developed motion film by putting on a dishwashing glove, wrapping all the film loosely around my hand, and then sticking it into big mason jars full of chemicals and counting off the time in my head. Somehow that seemed like qualification enough, that and my willingness to learn the tedious things that nobody else in the department wanted to do, and I got the job. Eventually I was transferred to the digital department, then just 70 employees strong, as the company wasn’t sure this computer thing was going to pan out. There is no way that could happen now for one of the technical positions. If you try to approach the place without an advanced degree in computer imaging, I imagine helicopters pick you off from the sky.

Laugh It up, Fuzzball

Now other houses—smaller, faster, able to take different kinds of risks—have eclipsed ILM, but at the time we were constantly redefining what it was possible to make real on the big screen, and being rewarded for it. But we still felt like a cowboy operation, a bunch of eggheads in T-shirts and jeans working out of a mismatched pile of unremarkable buildings in a forgotten corner of San Rafael. We’d say of models or shots or software that they were “kludged” together, but that spoke for the whole campus, composed of office buildings that had never been intended for the use to which we put them. We were sandwiched between a taqueria, a Circuit City, the unemployment office (convenient for the day after a project ended), and some trash-strewn wetlands that rewarded the lucky smoker with the occasional view of a heron or jackrabbit, which invariably looked fake after a day of virtual beasts.

It isn’t just animals, or the sky, or actual spaceships that start to look wrong when you become an FX geek. The whole process of watching a movie mutates. Your friends stop seeing movies with you unless they can ignore you vibrating in rage at badly executed effects and then sitting through the credits. All the way through the credits. Mumbling. At the special employee screenings a few days before the movies officially open, people show up at 10 a.m., coffee in one hand and popcorn in the other, and hiss at anyone who dares leave before the credits are over—opening that exit door lets the light in! As a new person, I didn’t expect a credit on Hook, my first film. But there was my name, spelled properly and everything; I was real. I’d really been part of this amazing project. (Yes, I am talking about a movie where Julia Roberts played Tinkerbell. Shut up.) I was so blissed out that I accidentally sideswiped someone’s truck in the parking lot afterwards.

Actors start to seem like a real nuisance. They move unpredictably, making creating effects around them tricky; Woody Allen’s twitching is cute until you have to remove a visible mic wire from his rippling rumples. Jim Carrey is a dream to draw lines around—when he moves, he does it very cleanly. When he’s still, he’s still. Actors don’t always care for effects folk either. Just before I started at ILM, an action star told Dave Letterman that the reason movies are so expensive isn’t actor’s salaries, but the union wages for the crew. Soon after, this gentleman came in to shoot some bluescreen. I don’t know if it’s true that once he was safely harnessed and dangling, several proud union members snuck out and spat on his car.

Do, or Do Not. There Is No Try.

When I was there, employees could read the scripts of the shows on which they worked. But when we started on the new trilogy, seeing the script wasn’t an option. Not that some of us wanted to, planning to plead plausible deniability on the Jar-Jar Binks question later. But when you don’t read the script and all you know about a film are the special effects shots, seeing the whole thing put together can be anticlimatic. Shots you labored on for days or weeks flash by in seconds, and there’s all that distracting dialogue and music and, well, mushy stuff.

There was a time-dilation effect to some of the work. Problems that didn’t get fixed the first time were now coming back to haunt us. On the Star Wars Special Edition, one of my officemates re-did a shot he’d worked on 20 years before. “I said at the time that if I just had a little more time I could do a better job,” he’d say. “Guess I got my wish.” He suggested icons for the credits—a baby’s rattle for the new people, a tombstone next to the names of those who had worked on the film the first time. I sat at my computer and added things, or made it possible to add things: banthas, backup singers, the windows in Cloud City. I made new shadows for Jabba’s sand barges, kludging a model out of index cards and toothpicks to hold under my desk lamp for reference.

The work could be tedious. I bitched and moaned about my job for years, especially after I developed the same hand problem that kept a local RSI clinic steadily stocked with my colleagues. And every time I tried to operate something that wasn’t a computer by “mousing” it, I wondered if I was losing my mind.

Some of the challenges were fun, and I always loved seeing my credits. I admit that wearing my company jacket into places where movie geeks would claw off each other’s limbs to get my digits was a nice perk. But mostly it was wonderful to work with such smart, creative people. Even if they did all have their own lightsabers. Or maybe because they did. Neeeeeeeoooooooowwwng.

San Francisco-based theater critic Lisa Drostova doesn’t like to admit that the opening bars of the Star Wars theme still excite her, 30 years later.