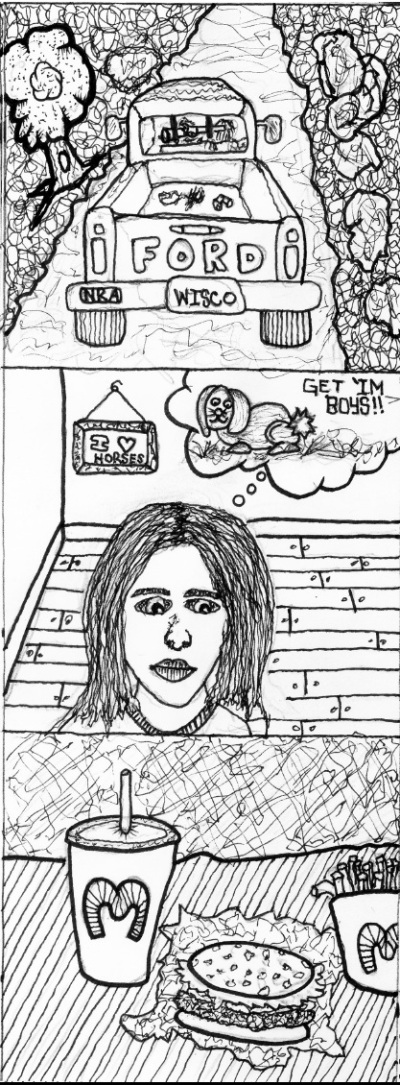

Vote With Your Gun

Hunter Ethics, Hunter Politics

by Elka Karl

illustration by Paul Panamarenko

ON A SUMMER morning in 1979, my father and I were driving across Highway 70 East in northern Wisconsin when a doe darted out of the scrub pine and hit the truck square across the front grill. My father released a string of colorful expletives and sighed, unsurprised. Hitting deer in rural Wisconsin is a seasonal occurrence at best; they terrorize the roadways like quadraped suicide bombers outfitted in buckskin.

Unfortunately, the doe didn’t die upon impact. My father told me I might not want to look. He pulled the tire jack out of the back of the pickup and bashed the deer’s skull in as I peeked through my fingers. When we drove into the next town to call the Department of Natural Resources to report the dead deer, my dad casually queried, “Elka, have I ever told you about the Hindu belief in reincarnation?”

I decided that the dead doe was, at that moment, being reborn as a beautiful desert pony. My father did nothing to disavow me of this notion.

In my life, I have killed one squirrel and a few handfuls of fishes. I have skinned or scaled these animals, gutted them and served them for dinner. I’ve also lent a hand in gutting several deer, though I was usually the person who steadied the carcass as my brother or father or friend split it down its belly lengthwise and pulled out its endless insides, like a magician unfurling scarves from a secret sleeve.

Of Dilemmas and Omnivores

I am an omnivore, and I buy most of my meat. Since I live in the urban inner city, my opportunities for hunting are limited. Still, at one point in my life, I spent most of my autumn weekends following my father around with a .22 shotgun cradled in the crook of my arm. Though I rarely shot anything, these remain fond memories, and I can’t imagine how different my family dynamic might’ve been if it hadn’t involved killing wild animals.

“I first went hunting with my brothers for chipmunks with homemade bows and arrows,” my father, Darwin Karl, recently told me. “Then [my brother] Max got a BB gun and we were in the big time.” The big time also involved my father’s procurement of a facial scar from a beebee that hit him between the eyeballs from a brother’s errant (or perhaps thrillingly accurate) shot.

Darwin traces our family’s hunting ethic back to our Saemieh (or Sami) great-grandfather. Sami populated the northern regions of Scandinavia for thousands of years; most people know them as Laplanders, or those funny white people with the reindeer. “They had a closer tie to the natural world and instinctively respected the animals more than most western cultures,” my father says. He likens this respect to that held by Native Americans for animal life. “Over the years I have had many Native friends and we relate well regarding this hunting ethic.” For my Uncle Perry, this ethic means bringing the bones and carcass of any deer he kills back to the spot where it died, and saying a prayer of thanks for that animal’s life.

(Not Really the) Thrill of the Hunt

Hunters have gotten a bad rap, especially in the last 30 years, when the public at large has simultaneously become more obsessed with the idea of animals and pets, and more disassociated from the source of the food they eat. Hunters are often portrayed as boorish, drunken rednecks who go for the thrill kill. This, however, isn’t necessarily the real story.

Michael Pollan tackles the topic of hunting in the last section of his book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, which explores this disconnect between meat eaters and the animals that provide that meat. He admits that he, too, was a victim of stereotyping before he became a hunter.

“The cliché is ‘Oh, they’re just getting away from their wives and drinking,’ but that’s too simple,” says Pollan, when we sit down to chat in his office at the Journalism School at UC Berkeley. “There’s something important going on there. There are easier ways to get away from your wife. [Hunting is] really hard work, it’s really inconvenient. … Cleaning animals isn’t fun. So my journalist’s radar should’ve told me ‘I should really figure out what this is about.’ But I entered into it a different way, which was through food, and creating this meal that I had hunted, gathered and grown myself. I was very lucky in that I found someone who was willing to take me into the brotherhood of hunters, however briefly. I’m really happy I did. It was one of the more formative experiences I’ve had as a human.”

As part of his research, Pollan hunted boar in Northern California with friend and hunting mentor Angelo Garro, a slow-food enthusiast and blacksmith living in San Francisco. Pollan describes the hesitation he felt surrounding the hunting experience, and his surprise at how much he actually enjoyed killing a pig.

“We have a real double vision about [animals],” says Pollan. “The animals we can see, we have very strong and sentimental feelings about them. At the same time we are thoughtlessly brutal in the way we eat animals and allow them to be treated on our behalf. It’s a very schizophrenic relationship. The animals we can see we treat well, and the animals we can’t we’re willing to let be brutalized. In the book I wanted to put more animals in more eye contact with people, so they understood that if they ate this way, this is what they were doing to animals. The more you learn about industrial meat production, the less tolerable and the less appetizing the meat is. And that’s why it’s so funny that people can find hunting so morally dubious at the same time they’re eating their McDonald’s hamburgers. There’s just no comparison between the life of a feedlot animal and the life of an animal that has the one bad day.”

Relative Changes

While Pollan hunts specifically to document the experience and to understand his own complicity in the taking of an animal’s life for sustenance, my family has hunted for survival for generations. During that time, my father has watched the American hunting populace switch from practicing responsible hunting ethics to embracing the aesthetics of trophy hunting.

“Most of my family has been at odds with the general hunting community because of the difference between our hunting philosophies,” says my father. “My brothers and I are extremely disgusted with the current hunting video industry. They are constantly showing the ‘kill’ and high fiving each other over this stiff animal’s body (which apparently was killed the night before, possibly in questionable circumstances) just to make a good scene for the film. It’s reprehensible!”

However, as the population in general begins to green its lifestyle and confront issues such as air pollution and climate change, it seems that the hunting industry is, perhaps, gaining some introspection as well. My father points to hunters’ education classes, mandatory in all states, as a vehicle for education and change in the hunting industry. “Hunters’ education classes will continue to change this negative side of hunting. You have to look at where the sport has come from in our country,” adds my father. “I mean, people thought nothing of killing buffalo out of train windows for the thrill kill … and that really was only a couple of generations ago.”

My father points to Dr. Saxton Pope and Arthur Young as two great influences in the ethical hunting movement. Pope and Young were responsible for revitalizing the art of bow hunting, and went on to form the Pope and Young Club, which has pledged millions of dollars towards conservation and hunter education over the past four decades.

When I speak with Pollan, he mentions the connection between hunting and land ethics, and the hunter’s essential need for an understanding of the terrain on which he is hunting.

“Hunting is a tool and hunting is a way of knowledge as well. You really have to understand a lot about an ecosystem to hunt successfully,” Pollan says. “It’s a way of knowing nature. And we know nature when we act in nature in a wholly different way than when we experience it as spectators. And that’s what I really admire. I’ve acquired a much deeper respect for hunters and what they know about food, and what they understand of the emotional complexities of it because you talk to hunters and they have complicated feelings about it—it’s not all glory. There are parts of it that fill you with remorse or shame or disgust, which I may have felt more intensely than others because it was my first time. But it was very real.”

And hunting may become even more real for more people. As humans encroach on wildlife territory and our suburbs become more and more rural, we also destroy habitat and natural predators. Given a dearth of wolves, bears and coyotes, it’s up to us to maintain sane levels of wild animal populations—often down the barrel of a gun.

“Hunters contribute huge amounts of money to preserving habitat. They are mostly conservationists. Harvesting the animals to prevent overpopulation is a necessary thing now,” says my father. “It really boils down to understanding the environment and the wildlife needs as well as the peoples’. We’re all in this together so we need to act appropriately.”

Elka Karl last ate squirrel at Christmas Eve dinner a few years ago. It was marinated in a homemade barbecue sauce prepared by her brother, who also shot the little tree rats.