This Is Not a Travel Essay

by Jessica Hoffmann

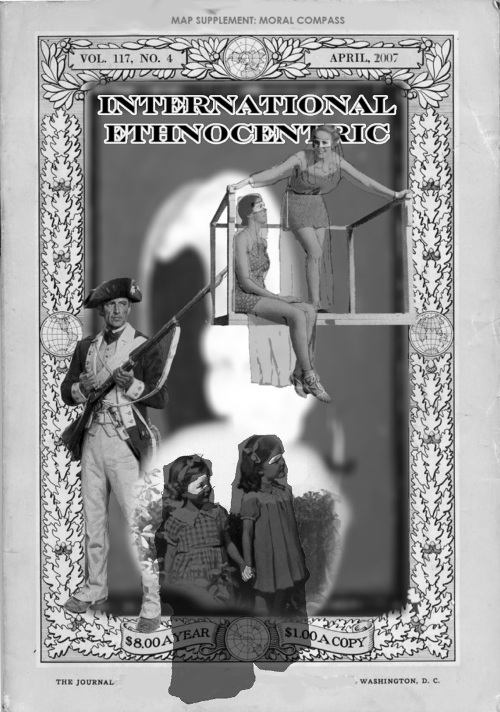

illustration by Tim Brown

We’ve been advised: long, loose garments that cover our elbows and knees (at least) and that don’t reveal any curves (especially not the hips and ass). Dressy sandals. No jeans (that means you, American).

As my friend models some outfits she wore on her last trip to the United Arab Emirates, I’m torn between enjoying the novelty of it all (nothing in my closet applies—it’s all too sloppy-tomboy) and feeling frustrated in my hunt for the “right” intersection of my critiques of binary gender systems and my critiques of the Western feminisms that would presume to know and judge the meanings of other cultures’ sartorial cus—

And then my friend, standing two feet from me, wraps her head and face in a black veil and my whole body revolts. Every muscle contracts and some deep internal voice screams, “No!” But that’s not what I say aloud. Aloud, I say, “Shit. This shit runs deep.”

My head is telling me that (as cultural critic Stephanie Abraham says) “to veil or not to veil” is not the question, but my body’s holding on to some fears and rigid readings of a culture I don’t deeply understand, and in the confusing space between my resistance to the gender oppressions I know and the culturally imperialist readings of Islamic culture I’ve been fed in these here United States, that body screamed “No!”

“It’s OK,” my friend says, admiring herself in her veil in the mirror. “We’ll only have to wear them if we go out into the desert. In Abu Dhabi, we won’t need them.”

Beyond the Veil

Our first day in Abu Dhabi, we go to the mall.

The international women’s leadership conference we’re here for doesn’t start till tomorrow, and there seems to be a lack of traditional tourist fare (museums, parks, etc.) in this new city. At first, I and the other U.S.-raised woman in our group (the other two, both Armenian, grew up in Iran) are alternately fighting and indulging our preoccupation with the different styles of hijabs and abayas moving on bodies through the shiny space, the teenagers draped in heavy black fabric browsing racks of brightly colored lingerie, the punkishly dyed hair of the girl next to me at the bathroom sinks and how casually she hid it beneath her headscarf in a single swift motion, the way (one of my Iran-raised friends points out) the teenagers wear their abayas a little too long to give the fabric a sexy bounce when they walk. We know better than to be so preoccupied with all this—so loaded, so easy for us to misread—but we can’t seem to help ourselves. We talk through this tension in whispers—

And then we realize that the women pushing the strollers wear clothes and headscarves of different colors than the solid black of the Emirati nationals, that the women pushing the strollers and carrying the bags, often a pace or two behind the strong-walking women in black, are mostly not Arab but South Asian. Right, right. Nannies. An immigrant serving class. It’s never all about gender.

***

My roommate and I small-talk with a bellhop in the elevator. Later, he knocks on our door. I let him in and then wonder if this is wise. He sits in a chair in the corner and tells us: He’s from Kathmandu. There are no jobs there. He came here through a migrant-worker agency, after paying a large fee. The hotel provides not only his job but also his housing, his meals, his travel to and from work. The worker residences are segregated by country of origin. He works long hours, he doesn’t make a lot of money, he would like to make it to the United States someday. He will e-mail us. (Six months later, he hasn’t yet.)

Talk Is Cheap

At the conference, the talk is rights-oriented, but in the bathrooms, young uniformed immigrant women are wiping the stalls to gleaming after each one of us delegates takes a piss. They’re working long hours, and, they tell those of us who ask, they’re not making enough to save or send much home. In the keynote addresses, established international leaders are insisting spiritedly that there is a place for women on the world’s grand stages, that we can succeed, that we can and should lead. A rep from Shell Oil narrates a slideshow about opportunities and diversity at her company. A Harvard econ student argues (in a pink button-up and blazer) that women need to stop being “nice” and learn how to negotiate for more benefits.

In the small panels, progressive and radical women (and people who may not identify as “women” in other contexts at all) from all over the world are finding one another. One talks in a small room about Spanish feminist anarcho-syndicalists. One challenges a speaker who condemns sex work as always and only devastating for women. One speaks of murders of maquila workers in Juárez, Mexico, and the need for international solidarity that does not demand sameness. Over and over, especially on the topics of female circumcision, sex work, and sharia law, delegates are struggling over the tensions between “universal” human rights and cultural self-determination, unjust systems and the agency of individual people moving through them.

Also, I’m starting to like the flowing garments and sparkly sandals I’m wearing. The tailored-soft-butch suits on the other American girls (the kind I’d admire at home) are looking very Western-businesswoman to me here. The gender-transgression code isn’t readable in this context; the only reading seems to be American Corporate.

Also, the veils are starting to lose their charge for me. Their differences are showing. Their wearers’ differences, too.

***

We take a day trip to Dubai, where, in spring 2006, one-fifth of the world’s cranes were located. We see them, huge, one after another, in demarcated swaths of desert on the other side of a stream of billboards promising the world’s most luxurious housing, office complex, whatever.

“Jesus, it’s a U.S. neocon’s wet dream,” I say, feeling clever. “Untrammeled development and no labor or environmental regulations to speak of; rigid gender roles and sexual repression to boot!”

It’s a disaster, is what it is. And by it I mean capitalism gone global; unsustainable development pushing us every instant closer to environmental catastrophes; rampant exploitation of migrant workers from the Global South. Take your pick for that it. I mean all of it and more.

It’s a disaster, and I’m smug. Suddenly all these pieces are coming together in my head, distantly read news registering sharp and close, and right alongside feeling horrified and compelled to take more and more action, I’m feeling smart and self-righteous.

Unlearning Process

Driving home from Dubai—being driven, rather, by a worker from India whose actual pay for this day (after his employer takes a cut of what we’ll give him) we don’t know—my friends and I talk about how seriously “to veil or not to veil” is not the question; we cover the subjects of war, global warming, migrant labor, Western eminism, imperialism. Two of my friends will return home in a few days to PhD programs; I’ll get back to making media. We talk about how much we have to write about this trip. We want to share things that feel important: This fresh, firsthand clarity that (of course we knew this before coming, but) there’s no binary clash of civilizations; rather, there’s a global mess in which lines of culpability are transnational, and there are pockets of people everywhere creatively working for and living alternatives. If we could get past nationalism and bottom lines and the isolated short-term, we could all—

And then: This is the elitism of the Left. We’ve experienced perspective shifts on this trip, and now we feel like we need to share our sharpened views, like that will be helpful, peace- and change-making, even. Yet our being here is in so many ways a matter of privilege—financial, educational, national…

And our belief in the positive-change-making value of spreading our newly expanded, elucidated perspectives is in some senses a very Western, colonial/imperialist belief. It reflects a faith in Enlightenment-style “progress,” the kind of benevolent “reason” and “humanism” that comes from world travel and a liberal education.

The problem, of course, is that world-traveling white Westerners don’t have the best historical record when it comes to increasing global harmony and cross-cultural understanding.

Falguni A. Sheth recently wrote in Color Lines that the “liberal self-deception that ‘reason’ can bring everyone … to a common culture … assumes that the causes of cultural and political disagreement are ignorance and misunderstanding … rather than a dominant imperious attitude that insists that the West is reasonable and coerces all others to conform.”

Also, to privilege the kind of “broad” view that comes from travel and cross-cultural experience and education is often to privilege the voices and perspectives of those who already have a good deal of class (and other) privileges.

Also, we don’t even understand very much. My little lessons from eight days on the other side of the world are so very, very small. I know and can speak to a meaningful little piece. So can the driver who’s silent before me, having made his different kinds of border crossings. So, too, his grandmother, who has never physically left her village.

Maybe part of what folks mean when they call progressives “elitist” is this: that we maintain hierarchies of experience and knowledge, that we use Enlightenment (i.e., European colonial) language like “progressive.” Whatever our values and political leanings, white Westerners still approach the world through a colonizers’ view. Every one of us does it. It’s running through each of my touring snapshots up there. It can’t not. It’s a view we’ve got to willfully, and continuously, unlearn.

Jessica Hoffmann presented a workshop on community-based media at the 2006 Women as Global Leaders conference in Abu Dhabi, UAE.