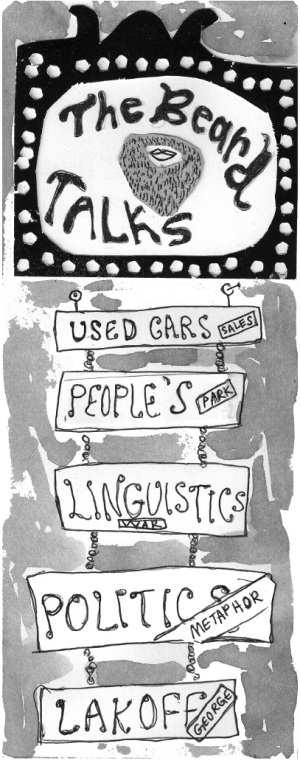

Metaphorically Speaking

An Afternoon with George Lakoff

by Ethan Strauss

illustration by Emma Spertus

The power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them. … To tell deliberate lies while genuinely believing in them, to forget any fact that has become inconvenient, and then, when it becomes necessary again, to draw it back from oblivion for just so long as it is needed, to deny the existence of objective reality and all the while to take account of the reality which one denies—all this is indispensably necessary. Even in using the word doublethink it is necessary to exercise doublethink. For by using the word one admits that one is tampering with reality; by a fresh act of doublethink one erases this knowledge; and so on indefinitely, with the lie always one leap ahead of the truth.

—from 1984, by George Orwell

We decide to meet at the Free Speech Movement Café. I squirm into the café’s endless line, waiting for George Lakoff to arrive. I’m nervous at this point, perhaps even scared shitless. Hell, he’s famous—famous for a linguist, maybe, but still: famous. Lakoff has penned best-selling books, founded the progressive think tank the Rockridge Institute and gotten involved in a full-fledged East Coast/West Coast rap-style feud with linguistics godfather Noam Chomsky. This is no scholarly dispute we’re talking about. In their spat over abstract theory, Lakoff said, “I see [Chomsky’s political work] as very much like his linguistics. Where he’s got a philosophical view of language and doesn’t apply it to real language.” To which Chomsky responded, “Die slow, mothafucka, die slow!”

If you’re prominent enough to piss off Chomsky, you’ve got clout.

At around 3:40 p.m., George Lakoff emerges. I choose my words carefully in this instance (and perhaps only this instance). A man like Lakoff does not simply arrive, he emerges. George Lakoff possesses the aura, the magnetism, the mystique, and, most importantly, the awe-inspiring beard requisite of a big-shot professor. I’m intimidated. This feels like a bad blind date, and Lakoff picks up on my unease. He knows he’s above me; there is no way I will ever impress him. A man with a well-manicured beard fears nothing. It’s one of the great mysteries of life; a man with a bad beard spends his evenings in Berkeley’s People’s Park, and a man with a great beard always appears to be one good idea away from a Nobel Prize. Is this justice, God?

“Are you going to stay in line for the coffee?” Lakoff asks, as I try to wish away the situation. I am stuck behind approximately 70 grad students and a Chinese New Year’s dragon. It’s an awkward circumstance. It feels as if the only way I can make the situation more uncomfortable would be to call him a “poseur Chomsky” or a “cunning linguist.” Trading one rough situation for another, we snag a table.

The Sound of One Man Rapping

Approximately one minute into the conversation it becomes apparent that Lakoff loves the concept of framing, which I’ve come to understand as the “use of an underlying metaphor as a means of communicating a concept.” As Lakoff jabbers that “what the conservatives have done is get their general ideas so their surface frames can be effective, so they can’t hang surface frames on them,” I start to feel as if I’m in Waking Life. I expect Lakoff’s beard to start shimmering and jumping across my field of vision.

During the entire interview, I can’t shake the feeling that Lakoff is on autopilot. I feel like the mirror in which he practices before he makes speeches. He often interrupts me and frowns when my question or comment disappoints him.

Lakoff does make some sense. Conservatives are good at using metaphors to connect with people’s deeper issues. They are also smart enough to use phrases like “tax relief,” “partial birth abortion,” and “liberal pussy-peacenik” to subtly brainwash us. I even agree with Lakoff when he claims that conservatives “lie effectively” when they propose bills like the “Clear Skies Initiative.”

The interview is going well since Lakoff is talking a lot, and due to that simple fact, the mood is marginally less awkward. Then something non-beard related occurs to me: My questions are contrived and boring. Contrived and boring! I have to do something about this. The stock answers to my stock questions are growing tedious. Somehow I actually conjure up a legitimate query.

“When you’re trying to get people to side with you politically, when do the ends not justify the means? When it is unethical, when is it lying?”

Tension fills the coffee-heavy air. Every pretentious café patron stops talking about what they saw on PBS last night and tunes in to hear Lakoff’s response to my master question. Stephen Colbert and Walter Cronkite simultaneously give me pats on the back as Lakoff decides how to respond. Bill O’Reilly tosses me his Polk award from across the room. Though I made up most of that (except Bill O’Reilly really was there and really did toss me his Polk award, I swear on my life), Lakoff’s response is one million percent not made up. He says, “I reject the question.”

What? Did he actually say that? I’m running on three hours of sleep and a Diet Coke, but I suddenly find myself wide-awake and curious as hell. When I beg him to elaborate, he says, “I reject the premise of your statement.” Jesus, this man actually is the cunning linguist. He somehow turns a question into a statement, enabling him to sidestep a sticky issue. Lakoff reiterates that getting someone to agree with you can be an honest feat. You merely have to say what you believe using metaphors, find out which metaphors work, and use them repeatedly. This is the old “the cars sell themselves” spiel that used car salesmen claim to abide by. If you have a good product, you don’t need lies or exaggerations to sell it. All you need is a firm handshake and some good, honest salesmanship. If you think I’m comparing Lakoff to a used car salesman, well, I’m not. It just really, really seems that way.

It doesn’t matter what linguistics theory you employ to explain it, this brand of thinking will kill you politically. Sure you don’t “need” trickery to sell your product, but it certainly helps. The tiny idealist in me wants to embrace this pro-honesty philosophy, but I just can’t. Thousands of years of human history are not on Lakoff’s side on this issue. Hell, I’m not sure if Lakoff is on Lakoff’s side on this issue.

Earlier in the interview he told me that conservatives are partially successful because they lie. “That’s part of [their success],” he said. “They use misleading language.” But now he’s saying lying doesn’t help? He’s like a microcosm of linguistic evolution; “not lying” and “lying” can mean the same thing in Lakoffian, given a suitable context (i.e. when he wants to be right). He says whatever he wants, whenever he wants, constantly.

Make What Is Unreal Appear Real

Towards the end of the interview, Lakoff adds to my doubts when he reveals that issues carry little weight in the voting booth. He recalls a conversation with former Reagan chief strategist Richard Wirthlin. Wirthlin apparently explained to Lakoff that many voters who supported Reagan didn’t agree with him at all. Lakoff says that they voted for Reagan because “they identified with Reagan, he spoke about values rather then issues, they trusted Reagan, and they found him authentic.” When Lakoff tells me that this strategy helped propel the Gipper to power, I have to interrupt the bearded one and ask him another biggie.

“So, do issues matter?”

He pauses, his brow furrows a bit, and he conducts a mental Google search. The sun is starting to set, and the mood of the interview is a little more relaxed than it was earlier. Maybe he’s warming up to me; after all, he just told me an anecdote. Next he’ll let me sit on his lap. This could be it—this could be the moment where I get some candor. The brow unfurrows and Lakoff confidently says, “They matter symbolically.”

Dang it, perhaps I wanted the candor too much. I sit there for a beat and pretend to let his statement sink in. I’m stumped. Dejected, I move on to other questions.

Ironically, his anti-lying stance leaves me feeling hoodwinked. If issues are meaningless, then how are you supposed to honestly sway voters? If you’re persuading people with something other than pure facts, how is that not manipulation of some kind? His explanations are confusing me and I get a bit suspicious whenever the beard gives me a wink. I ask him, “If issues don’t matter, then how much of the difference between the two parties is arbitrary?”

“I don’t know what you mean,” he says, a bit defensively. He recovers his composure and tells me that the “dichotomy is part of the American culture.” I’m getting the ultra-furrowed-brow-with-the-frown-face right now. He goes on to say, “It’s wrong to think of these things in terms of issues, they should be thought of in terms of arguments.” Needless to say, I have no response for that one either.

This is how the rest of the interview goes: I ask a question, Lakoff picks me up out of my chair, throws me into a vat of verbal quicksand and laughs maniacally as I sink to the bottom while frantically attempting a slow, awkward doggie paddle.

I’ve been winging it for most of the interview, and I finally run out of steam. After Lakoff goes on a diatribe about the changing definitions of “conservative,” my mind freezes up. When the rant ends, Lakoff waits for another possible question. The long pause is too uncomfortable for me to handle. Lakoff’s looking impatient and his beard is tapping its foot. It’s obviously time to end this thing.

As I walk away, I can’t shake the suspicious feeling that Lakoff was using his mastery of linguistics as a means of evasion. Maybe he just doesn’t want to deal with the difficult moral dilemmas that come with being a politician. Maybe he wants to help the Democrats win and, by presenting a clean image, is part of that strategy. Whatever his motivations, I sense that Lakoff knows a bit more then he’s letting on. I just wish he would let me in on the secret instead of hiding behind his perfect beard and abstract language.

Maybe I’m being a bit hard on Lakoff. He does have a good platform, even if much of is a bit intuitive. But it’s not bad advice. Even if I’m not hopping on his framing bandwagon, I have to admit that he’s dead-on about the Democrats’ need to convey their messages better. I’m just not sold on the philosophy that it is possible to manipulate without manipulating—something’s not right. I can’t say what, but it doesn’t click. Not right now, anyway. However, if Lakoff gets in a fist-fight on CNN’s Crossfire with host Tucker Carlson, I’ll believe anything this man says.

Perhaps this is what the Democrats need: a liberal Karl Rove (with less immorality and inherent evil). Lakoff could provide Democrats with a political tactician who professes complete veracity while simultaneously mind-warping the masses. Whether this is something to hope for, or something to fear, goes back to the question I’d posed earlier to Lakoff: When do the ends justify the means?

In our interview, Lakoff accused the Republicans of using Orwellian language to deceive voters. At the moment he made this accusation I was reminded of Orwell’s doublethink concept. As another George (who was quoted in the epigraph to this essay) once said, “If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” Which leads a young, dumbfounded journalist to paraphrase the Great Emancipator:

You can deceive all of the people part of the time, but if part of those people talk to a linguistics professor for 50 minutes, they’ll probably just get really fucking bewildered all of the time.

Ethan Strauss is a sportswriter/apathetic Berkeley student. When he’s not contributing articles to Dime Magazine, he’s usually watching The Wire or playing Madden 2007. Some would say he’s the greatest American who ever lived. They would be quite correct.