Scraps, Part One

Life In San Francisco’s Adobe Bookstore

By Gravity Goldberg

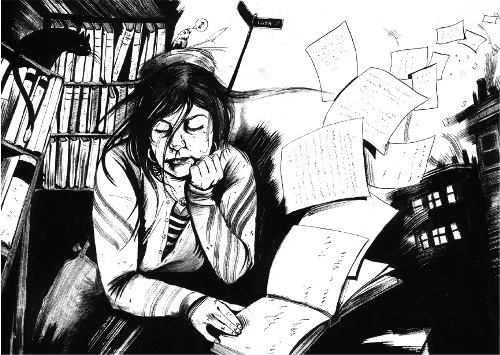

illustration by Chris Lane

Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories. …[T]hus there is in the life of the collector a dialectical tension between the poles of disorder and order.

—Walter Benjamin

ON MOST Sundays, I’m behind the desk at Adobe bookshop in San Francisco’s Mission District. Piled on the desk are books, plastic toys, an overflowing dish of foreign coins, a crystal ball and three out-of-date globes.

When, back in 1997, Utne Reader voted the Mission the second hippest neighborhood in the United States, the cover of the issue had a drawing of a dreadlocked bike messenger chilling with his bike in front of Adobe. The not-so-subliminal message seemed to be that Adobe was the heart of all this hipness. I have since wondered if the illustrator’s choice was a random coincidence, or if he had an inkling that, even as the Mission underwent the ravages of gentrification, this place would remain reasonably unscathed, just as unpretentious and eccentric as it has always been.

From behind the cluttered desk, I peer outside at the 16th Street pageant of beautiful hipsters probably strolling towards TiCouz or The Pork Store for hangover brunch. Predictably, one or two of these groups will dart into the store for a moment, with what I presume to be an out-of-town guest in tow. The brief conversations are always remarkably similar, as is the tone of propriety: “Oh darn, it’s gone! Remember how I told you about the bookstore that organized its books by color?”

The Rainbow Collection

A few weeks after 2004’s Election of Despair, when so many San Franciscans were walking around in a perpetual gloom that had nothing to do with the fog, artist Chris Cobb entered Adobe one night after closing, along with a small group of volunteers, and by morning they had reorganized the entire inventory of the store. The traditional method of bookstore organization—fiction, history, politics, etc., kept in separate sections (although Adobe was never known for being particularly well organized)—gave way to an arrangement by color. A rainbow of books spanned along the western wall of the store. It was the brightest and most joyful spectacle to be seen in the city during those months. After NPR aired a brief interview with Chris, hundreds of people came from all over California and beyond to browse the store, taking in the simultaneously random and exquisitely well-ordered installation.

As these visitors shuffled into the store, I sat behind the desk fielding questions. Mostly folks just wanted someone else to affirm what they were seeing. Often they were unwilling to trust their own perceptions. They’d lean over the desk and inquire, “The books are arranged by color, right?” Although a smaller, more confident few conjured up their own explanations, such as the man who was convinced that we’d painted the books, or the woman who insisted we used colored lights. But my favorite response was reported to me later. A white-haired gentleman hunched over, scrutinizing the section of brown books under the wooden history sign, discovered a grouping of four or five books about the American Revolution. Amazed, he double-checked the sign and then turned toward my friend and remarked, “Astonishing—the books here are arranged by both color and category!”

Chris’ project hadn’t been a surprise. Just like any momentous installation, it took months of planning, and at each step of the process I warned him that this was the worst idea I’d ever heard. That to disorganize the store was like forcing it to commit consumer suicide; that once the books left their homes it would be a task amounting to Hercules cleaning the Aegean stables to ever return them to their proper homes. He casually assured me that contrary to my skepticism, he had an excellent and well-thought-out plan. In each book he would place a small tab of paper, with a tiny diagram of a bookshelf, on which he’d mark the row and shelf from which the book had been moved. I ground my teeth but hoped I was being overly cautious. The day I walked into the store and first laid eyes on the installation, though, I felt that no matter what the consequences, they were worth it. The bookstore was breathtakingly gorgeous. However, every time a browser flipped through a book, the scrap of paper fluttered out, littering the floor with hundreds of them, like a blizzard of dandruff, or orphaned jigsaw pieces of a thousand different puzzles. My fears turned out to be justified. Months later, although the store was still rainbowed (long after the planned week-long run), the interested crowds had dwindled, and all that was left were the regulars who’d walk in, and with a huff, exclaim “I still can’t find anything,” and storm out. Almost two years later, the store is only beginning to find its way back to order.

Book People

I usually spend the early hours of my Sundays sorting through stacks of fiction scattered in piles all over the store. Cherry-picking rare classic fiction, and newer popular titles, I cram them onto the overcrowded fiction shelves. As the morning fades into afternoon, my salon assembles: a group that comes by every Sunday to hang out while I am working. My salon is mostly composed of men over the age of 50, erudite men overflowing with historical minutiae and fascinating information. They position themselves on the old couches, chattering about obscure trivia like it’s juicy gossip, and resume half-decade-long arguments about Hegel or the subtle ideological differences between local Communist camps.

The average Sunday conversation is as interesting and diverse as if the entire Encyclopaedia Britannica began to speak and do cartwheels. Last week’s discussion included the demise of the royal court of Austria, Plath’s and Hughes’ abusive relationship, and Zizek’s definition of the Social Order. I sit listening, chiming in a little from time to time, but eventually my attention wanders; my ability to upload information is not as fast as their inclination to download. I begin to look around for distraction. If I’m lucky, and we’re on speaking terms, I’ll find my on-again, off-again lover of eight years lurking around the history section, and I can go flirt or argue with him. We’ll hide behind the stacks of books—only peeking out every so often to check on customers—while carrying on our own long-running conversation about Christopher Hitchens or Frank O’Hara’s poetic predecessors.

Other times the Artists will converge, never supplanting the men on the couches, just adding their own inquisitive twists to the blustery conversations—Adobe is still more or less the heartbeat of what is known in art circles worldwide as the Mission School, an eclectic group of urban artists who incorporate the hurly-burly scraps of city life into their artistic narratives. Maybe one of the local musicians who hang out here will pass through: the crepuscular starlight of John Dwyer, the supernova of Devendra Barnhart. Once, celestially tall Thurston Moore wandered in looking for homemade poetry chapbooks. I didn’t recognize him until my friend scribbled on a scrap of paper and pushed it across the desk to me: That’s the guy from Sonic Youth. I dropped the note into the desk drawer. Later that night, Mission School artist Chris Corales, spoke to him at an art event and mentioned the store. Thurston, thinking about it for a second said, “Oh, you mean the smelly bookstore.”

The smell is unbearable. Even before Leo the cat—brought in to control the mice—peed on every Oriental rug scattered throughout the place, it stank. The comfortable chairs invite neighborhood intellectuals and artists, but the sleepy, stinky, homeless make themselves comfortable as well. And the books, lest we forget the books, are entropic, exuding a musty odor of decomposition and dust.

Others blame the smell on our Messiah, Swan. He lives in a nook in the back of the store and smokes thin brown cigars. Hunched over his Eliot Fisher, he types out his daily missive: La Flambé—a rant about rats, Jewish conspiracy, parking meters and pigeons. Katz Bagels, across the street, used to donate dayolds for Swan to feed to the pigeons, until the neighbors complained. Pigeons have surprisingly long memories; they still fly into the store looking for their daddy.

Someone always asks about Andrew, the beloved owner of the store. Without him none of this could exist. He possesses old-world grace and manners coupled with an extreme interest in all sorts of people. He looks at you through luminous blue eyes focused on some romantic moment of the past. Every day he sports one of his ever-growing collection of hats, and if you coyly plead, he’ll sing an old-fashioned barbershop tune in his lovely tenor voice. He is the ultimate host and curator, inviting in future mayoral candidates as well as the developmentally disabled adults from Creativity Explored across the street. Over the 15 years of Adobe’s existence, I think Andrew personally welcomed into the fold every one of the thousands of people who feel a protective kinship to the store. His introductions have led to marriages. I have at least two ex-boyfriends whom I met through Andrew. Yet he also has a wily side. He slyly and subversively dismantles. He oversees the struggles between poles of disorder and order, which is what makes this place so great, but also makes it impossible to regard it as a fully functioning business. Some see it as a form of self-sabotage. But without these conflicting impulses, his store wouldn’t have become a legend. He prioritizes community over commerce. After all, what kind of business owner allows his inventory to be transformed into a work of art?

Part Two of “Scraps” appears in R:evolution, p. 90.

Gravity Goldberg is the editor of Instant City: A Literary Exploration of San Francisco. She dedicates her essay to the memory of Bart Alberti, the brilliant flâneur and poet. Without his daily updates, bookstores in San Francisco have not been the same.