Art School Confrontational

Jon Rubin and the Independent School of Art

by Stephanie Young

ONE OF my favorite local literary cultural-historical moments took place in the late ’70s, when Robert Gluck, then director of Small Press Traffic, began a series of free, walk-in workshops in the back room of SPT’s bookstore at 24th and Church Street in San Francisco. The thinking and learning they did there, outside of the still-nascent academic creative writing classroom, was unruly, complicated and deeply committed. It’s a model I had in mind when I first thought about the Independent School of Art, a project Jon Rubin started in San Francisco a few years ago. The ISA takes its form as content, inhabiting a malleable idea of “school,” all the while demanding rigorous commitment from students and faculty. The ISA is serious play.

This is a school that assigns all students the same introductory project: Earn $100 in one week without getting a job. Students have sold everything from banana bread at the Pride Parade to one-dollar compliments. Others have recontextualized cash donations (“surrendered a birthday check from my mom”) or failed (reselling furniture obtained for free on Craigslist; that particular story ends with the smashing of a black lacquer armoire the student couldn’t even re-give away). Ever-present risk of failure, scrappiness, creative exchange—like everything the ISA does, the $100 assignment enacts the school’s pedagogical principles. The money goes towards the school budget, but as Rubin says, it also serves as “a miniature version of the do-it-yourself nature of the school.”

Seen as part of Rubin’s art practice, the ISA is “in many ways … a very traditional work made up of a series of living elements—students, teachers, cultural expectations, economic structures, pedagogical philosophies—that are developed into an evolving composition.” Just as each ISA project, or session, seeks to question and engage the conventions of a given frame (the gallery, the fundraiser, the lecture series, the flea market) in a new way, the ISA engages its educational frame from every imaginable direction. The most visibly radical departure from its given frame is economic. There’s no tuition, but it’s not free, either; the school relies entirely on the barter system. No grants, no institutional support, no wealthy patrons. Students, who are selected by Rubin, must agree to at least 10 hours of barter service for the school or faculty. By dispensing with that mediating body known as the administration, ISA renders the exchange of educational labor explicit, and relationships between students and faculty are made more personal.

Bryan Kaplan, who has been an ISA student and its event coordinator for the last two years, initially dismissed the idea of the school as Marxist and utopian. He says he watched while “about 30 other dedicated artists eagerly applied … and Jon brought aboard Bob Linder as a second teacher to split the load. Bob is one of the (other) most insightful and helpful teachers I’ve ever had, and he enrolled me unapplied. Flattered, I graduated from SFAI in May 2004, transitioned almost immediately into ISA, and never regretted joining.” Kaplan says the personal relationships generated by the barter system “fostered a greater sense of responsibility for each of us as both students and artists. Those qualities are essentially absent in the traditional model of education, and the ISA was a proof-of-concept that such a structure is viable, at least on a small scale.” These closer working relationships “quickly led to our collaborating on large-scale labor-intensive events. We produced two in our first session. They were extremely ambitious events that no one person could create alone. That sort of camaraderie is certainly more typical of collectives than of schools.”

With no tuition, it follows that the ISA has no permanent space. For Rubin, “being nomadic, or space-less, was another important pedagogical situation that I felt was healthy for an art school and its students to negotiate. There are plenty of resources out there already that we just co-op for our use, from living rooms and restaurants to empty school classrooms and under-attended art galleries.” It’s an example of what he terms “redirecting the stream,” and it’s a central mode of his art-making.

It’s tempting, when thinking about the ISA, to compare and contrast it with the academy system at every turn. For instance, on the subject of degrees: The academy grants them. The ISA? Fuck no. “No one really gives a shit about your degree,” Rubin says. “In my entire career no one has ever asked for my degree. … What are they going to find out from it? I technically got my masters degree in painting, but never got near a painting my entire time in school.” In a world where “most folks who go to art school won’t become Matthew Barney” yet still spend or borrow the money to go to art school, the ISA exhibits a radically different model of education.

Which doesn’t mean Rubin’s, or the ISA’s, relationship status with the academy and other art markets isn’t complicated. I heard from some current students how one of their peers had recently been accepted into a top-tier graduate art program based on her studies at the ISA, although other students could care less about formal education or art-world connections. (Most talk about how transformative the school has been for their individual art practice.) Another current student told me that one reason she pursued studies at the ISA was because it offered an affordable alternative to a more traditional art school.

Rubin recently moved to Pittsburgh to teach at Carnegie-Mellon’s School of Art, where I imagine someone like a provost or dean might have asked about that degree. As to how he might redirect the stream while more permanently housed in an institution, Rubin explains: “It’s still very early, but I’ve already had discussions with the department about getting a coverall insurance policy that will allow me to work with the students in almost any context we can think of. I’m interested in experimenting with and stretching the experiences and discourses I have with my students. Maybe creating a free-zone that tethers itself to the school but functionally exists more directly in the world.” It’s also a transitional moment for the Bay Area ISA, which is reorganizing into something more like a teacherless school, or a collective arm called DOCE (Department of Continuing Education.) When I sat down at the DOCE’s table at the Latin American Club this week, their first official meeting since Rubin left for Pittsburgh, and asked what it was like with Jon no longer in the Bay Area, someone joked, “We need a leader! Will you be our leader?” We talked about various clichés and conventions surrounding the idea of continuing education and how ongoing projects might riff on that form in the same way the ISA riffs on formal arts education.

The DOCE is currently in the planning stages of a project at New Langton Center for the Arts, where its members will serve the food at a fundraising dinner, and in exchange can do any art they’d like in the space that evening. According to this arrangement, they’ll directly engage a population they haven’t dealt with before: the patron. The project is still in its planning stages, with the group thinking about how to investigate notions of reciprocity, anonymity and historic patron-artist relationships.

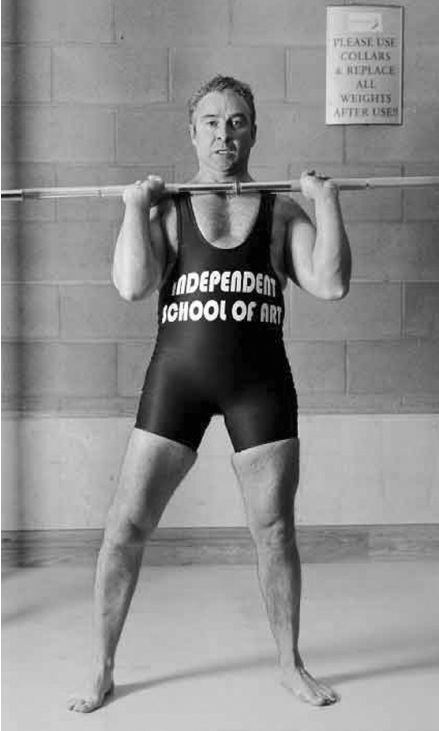

This opportunity is itself the result of another exhibit the group put up at New Langton earlier this year, involving recreations of performances at Langton from the ’70s and ’80s. Reciprocity is built into the double helix of the ISA/DOCE. A good example is the Liam Beville Fan Club which Rubin worked on with ISA students Bryan Kaplan and Naomi Miller after being invited to participate in an exhibition in Ireland. “At the time of the invitation I was already wrestling with how to present the ISA project in different venues and situations,” says Rubin. “I decided I would try getting someone in Ireland to act as a sort of proxy or Trojan Horse for disseminating information about the school.” The show, based around the theme of generosity, reminded Rubin of the local deli that sponsored his little league baseball team when he was a child. The deli “got a little bit of advertising, and we got to have our team photo in the deli, which we would visit after every game. It seemed like a good relationship.” The search for an affordable and interesting sponsee led Rubin to Irish powerlifter Liam Beville, whom he approached with the idea of creating a “mutual admiration society.” If Beville would advertise the ISA on his powerlifting suit, Rubin and the ISA would create a fan club site about him. The result? “He was completely game. In addition to wearing the suit during competition, I had a mural size photographic banner of him wearing the suit placed in the exhibition next to a computer that displayed the fan club site, which just so happened [to be] embedded inside the ISA website. Needless to say, we’re big in the town of Limerick, Ireland right now.”

Stephanie Young is employed by Mills College but she’s also a member of the Totally Unaffiliated Lacan Reading Group.

Photo One: Liam Beville Fan Club

2006

Photo Two: School In Session

2006